“An artist is not special,” according to Japanese American artist Ruth Asawa (1926–2013). “An artist is an ordinary person who can take ordinary things and make them special.”

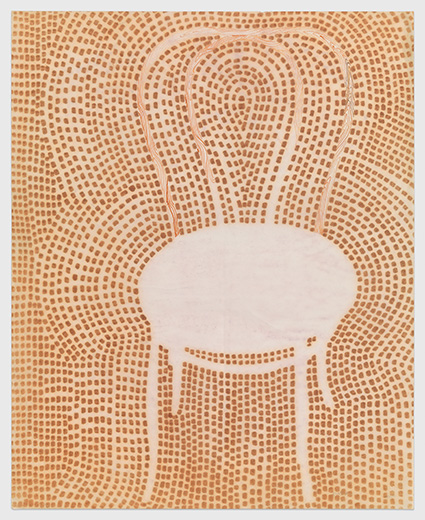

Born in Norwalk, California, to Japanese immigrants, Ruth Asawa’s childhood revolved around the eighty-acre farm that the Asawas tended (on lease, due to discriminatory laws that barred them from owning land). Though she showed an early interest in art, Asawa and her six siblings had little time for hobbies; there was always work to do on the farm, and the Great Depression left little money to spare for lessons and materials. Still, Asawa would find a way to make these “ordinary” experiences special: “I used to sit on the back of the horse-drawn leveler with my bare feet drawing forms in the sand, which later in life became the bulk of my sculptures.”

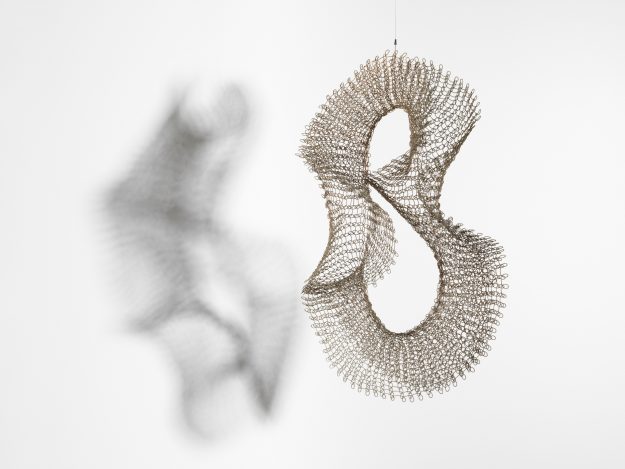

But ordinary life would soon change for Asawa. In 1942, she and most of her family were incarcerated at the Santa Anita Park racetrack, in the San Gabriel Valley. Her father was sent to a different camp, in New Mexico, and she wouldn’t see him again until 1945. Having to sleep in filthy stables, amid bleak conditions, the teenage Asawa turned to art for comfort, practicing her drawing with fellow detainees, including some former Disney animators. Six months later, the Asawas were moved by train to the Rohwer Relocation Center in Arkansas. During the train ride, Asawa spent every evening absorbing the night sky and the desolate landscapes of the rural US. These images, along with swamplands surrounding Rohwer, would later possibly inspire some of the swirling motifs and branching forms seen in pieces like Untitled.

In 1943, Asawa was granted a Quaker scholarship that permitted her to leave Rohwer and attend Milwaukee State Teachers College with the goal of becoming an art teacher. But three years in, lingering anti-Japanese sentiment prevented her from completing the student teaching requirement she needed to receive her degree. At the suggestion of friends, she traveled to North Carolina and enrolled in the summer session at Black Mountain College, an experimental liberal arts college. That summer, she honed her painting and drawing skills, and found herself so energized by her studies that she stayed for three more years. Under the tutelage of the influential German painter and former Bauhaus educator Josef Albers, as well as other teachers including Buckminster Fuller and Max Dehn, Asawa grew significantly as an artist, developing a rich portfolio of colorful, swirlingly abstract works.

It was at Black Mountain that Asawa met her future husband, architect Albert Lanier. Lanier left North Carolina for San Francisco in 1948, and Asawa joined him the following year. The two married shortly after in the summer of 1949. In San Francisco, Asawa continued experimenting freely with her work: “My curiosity was aroused by the idea of giving structural form to the images in my drawings,” she said. “These forms come from observing plants, the spiral shell of a snail, seeing light through insect wings.” During a 1947 trip to Mexico to volunteer as an art teacher, a local craftsman taught Asawa how to make egg baskets by weaving wire. This technique was highly influential on Asawa, whose looped-wire sculptures would go on to garner early recognition in the 1950s.

“Art is for everyone. It is not something that you should have to go to the museums in order to see and enjoy.”

Though busy raising her six children, Asawa continued to create, often late into the night, and fiercely advocated for the arts and arts education. She founded the Alvarado School Arts Workshop, an innovative program aimed at introducing children in San Francisco–area public schools to various forms of art. At its peak, the workshop ran in fifty schools and employed professional artists, musicians, and gardeners. Much of Asawa’s passion for arts education was rooted in her own childhood experience with the freeing power of art amid adversity. Later in life, when asked about her internment experience, she said, “I hold no hostilities for what happened; I blame no one. Sometimes good comes through adversity. I would not be who I am today had it not been for the internment, and I like who I am.”

While she exhibited her work at institutions like the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Asawa was also granted a number of public sculptural commissions, including a controversial fountain depicting a nursing mermaid in San Francisco’s Ghirardelli Square. In the 1980s, Asawa opened a public high school for the arts in San Francisco. Her stance on art’s accessibility was clear: “Art is for everyone. It is not something that you should have to go to the museums in order to see and enjoy.” In 2010, the school was renamed the Ruth Asawa San Francisco School of the Arts. Asawa died peacefully at home three years later, at age 87.

A selection of Asawa’s works on paper and sculptures is on exhibition at the David Zwirner Gallery in Hong Kong through February 22. “Ruth Asawa: Retrospective” will be on view at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art April 5–September 2, 2025; the Museum of Modern Art in New York October 19, 2025–February 7, 2026; the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao March 20–September 13, 2026; and in Switzerland at the Fondation Beyeler October 18, 2026–January 24, 2027.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.